The Fabric of Agency: Philosophical Insights for Agentic AI

Artificial Intelligence is entering a new phase. Foundation models like GPTs have been celebrated for their generative capacity: ask a question, get an answer. But increasingly, researchers are realizing that raw prediction power is not enough. What matters now is agency – the ability of AI systems to act, reflect, plan, and collaborate in ways that echo human patterns of behavior.

Stanford’s Andrew Ng has predicted that agent workflows may drive more progress than the next generation of foundation models. That’s a bold claim, but one that reflects a profound shift: AI is no longer just about output, but about process, structure, and autonomy.

In this blog post, I’ll explore what agentic AI means in practice, and then zoom out to ask a deeper question: What does philosophy tell us about agency itself? Are we right to call machines agents? Can they ever be moral beings?

From LLMs to Agents: Four Patterns of Agency

Traditionally, LLMs were used in a zero-shot fashion: prompt in, response out. That works well for certain tasks but misses the iterative, self-reflective nature of human reasoning.

Agentic workflows change that by layering structure onto the model’s generative powers. Andrew Ng identifies four recurring patterns that significantly improve performance:

Reflection: Models re-examine their own outputs, spotting errors or inconsistencies.

Tool Use: Instead of hallucinating, agents can call external tools (like web search, calculators, or code interpreters) to ground their results.

Planning: Breaking complex tasks into smaller, sequenced steps.

Multi-Agent Collaboration: Agents ‘debate’ or divide tasks among themselves, just as human teams do.

Experiments show that these patterns can substantially boost benchmarks like HumanEval, which tests programming ability. The lesson is clear: agency amplifies performance.

Inside the Architecture of an Agent

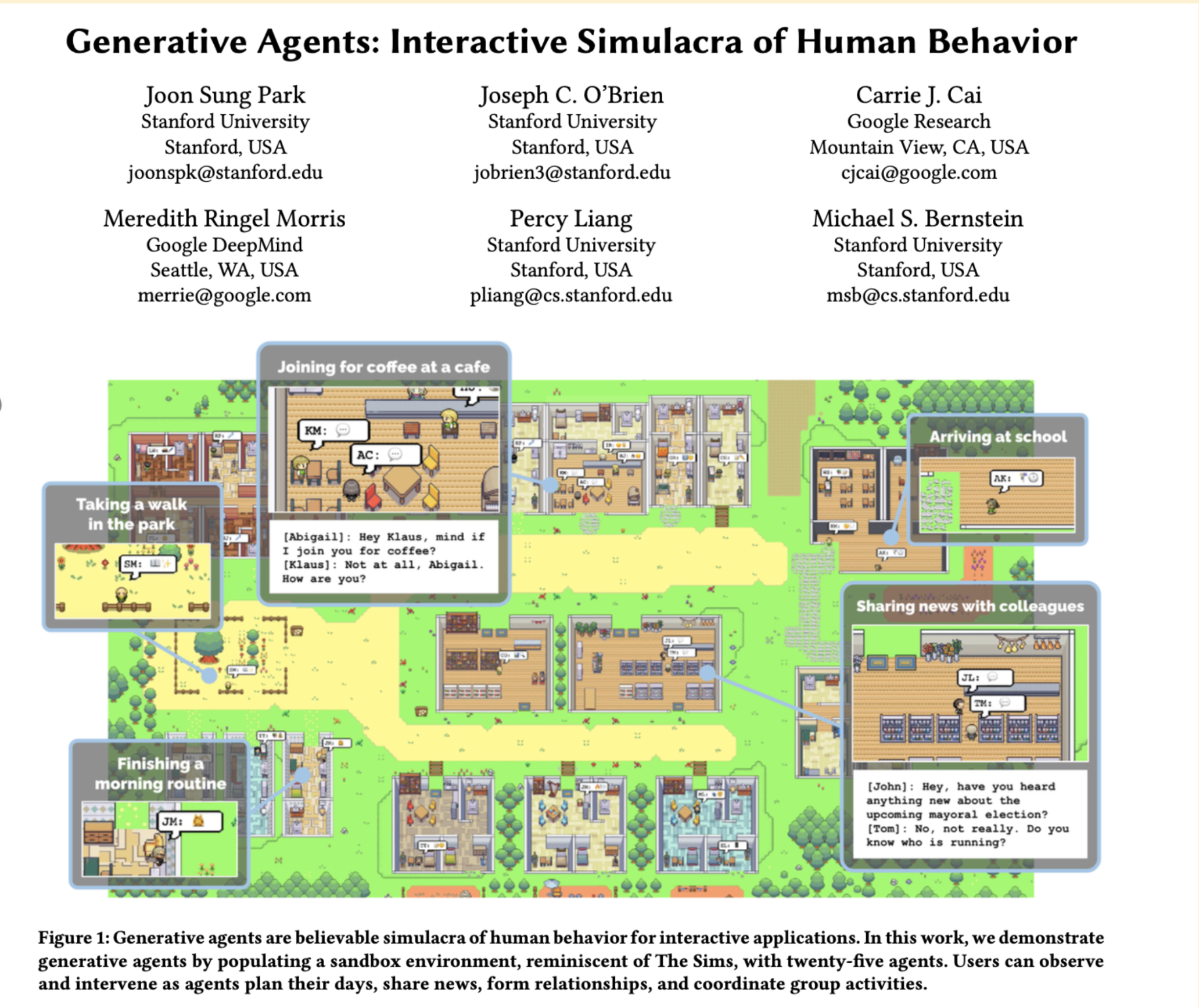

One of the most compelling implementations of agentic AI comes from Park et al. (2023), who built a simulated world populated by generative agents. Each agent runs on an LLM but also has memory, reflection, and planning capabilities.

Memory streams store observations with timestamps, weighted by recency, importance, and relevance.

Reflection modules allow agents to generate higher-level insights from their experiences.

Planning systems guide agents’ future actions, creating coherence over time.

When tested, human evaluators rated agents with the full architecture as more believable than stripped-down versions. This suggests that raw LLMs are not enough – agency requires scaffolding.

Even more fascinating, when agents were placed in multi-agent settings, they displayed emergent behaviors: spreading information, forming relationships, and coordinating with one another. In just two simulated ‘days’, information seeded in one agent had diffused to nearly half the population. That’s not just computation – it looks a lot like a community.

Philosophical Detours: What Is Agency?

Of course, calling machines ‘agents’ raises an old philosophical question: what does it mean to have agency?

Philosopher Donald Davidson (1963) offered a simple but powerful view. For Davidson, an action is something we do for a reason. If you flip a light switch to illuminate a room (and perhaps unintentionally alert a prowler), your action is explained by your desire-belief pair: the desire to see, and the belief that flipping the switch will achieve it. Daniel Dennett later framed this as the ‘intentional stance’ – we can explain behavior by attributing desire-belief pairs in terms of intentions.

But humans might have something more. Harry Frankfurt (1971) argued that we are distinguished by second-order desires: the ability to not just want things, but to want to want them. An addict who resists a craving because he wants to be free from it demonstrates this reflective self-evaluation. Frankfurt called such beings persons. By contrast, those who only follow first-order desires – whether animals or ‘wanton’ humans – lack this higher agency.

This is a critical line: if agency involves reflective self-evaluation and adaption, can existing AI models truly qualify?

Robots as Moral Agents?

Philosopher Catrin Misselhorn (2013) offers a nuanced take. She suggests that agency is not all-or-nothing but exists by degrees, across two dimensions:

Capacity to act for reasons – acting in ways guided by goals or representations.

Self-origination – being able to act flexibly, not purely determined by external programming.

By these measures, many modern robots – and especially agentic AI systems like Park’s generative agents – already qualify to some extent. They can process information, adapt their behavior, and even learn from experience.

But what about moral agency? Misselhorn defines this simply: acting for moral reasons. If agency comes in degrees, then so too might moral status. That thought carries weight. If we grant AI systems even partial agency, do we owe them recognition as moral patients – beings worthy of ethical consideration?

Shared and Collective Agency

Philosophy also reminds us that agency is not only individual. Groups – parties, organizations, even companies – can act in ways that go beyond the sum of their members. This raises fascinating questions for AI:

What does it mean when multiple agents collaborate, forming emergent group behaviors?

Can an AI collective have intentions, or only its constituent agents?

If moral agency implies moral patienthood, what does that mean for societies of machines?

Similarly, Marvin Minsky once imagined the ‘society of mind’, where intelligence arises from countless simple processes working together. Agentic AI may be the first step toward making that metaphor real.

Final Thoughts: The Coming Debate

We are only at the beginning of the agentic AI era. Today’s agents can reflect, plan, collaborate, and remember. Tomorrow’s may evaluate their own desires, align with values, or even participate in moral reasoning.

Whether we see them as true agents or just sophisticated simulations, they force us to revisit fundamental philosophical debates:

Can machines ever have second-order desires – or is that the essence of humanity?

If agency comes in degrees, where do we draw ethical lines?

Agentic AI is not just a technical breakthrough. It is a philosophical challenge, urging us to reconsider the nature of action and choice.

As Andrew Ng suggests, agency may shape AI’s near future more than scale alone. But as philosophers remind us, agency is not just about performance. It’s about self-determination, responsibility, and moral worth. The question we now face is not only what agentic AI can do but what kind of beings we are willing to acknowledge it as.